We tend to think of cemeteries as static features of the cultural landscape – a dead stop for our forebears. In actuality, every cemetery is in constant, albeit slow motion. New interments, foot traffic for grave visits and by those in search of quiet contemplation, animal life above and below ground, and all the while gravestones and monuments molder and erode. Intent on living our everyday lives, we may only give such final resting places a passing thought, but cemetery preservation and maintenance are critical activities that keep these commemorative places alive and well for our future reference.

Over the past few years Hunter Research has continued to specialize in cemetery studies, usually in support of efforts to protect and increase public awareness of the importance of historic graveyards. In our hometown of Trenton, with funding support from the New Jersey Historic Trust we have completed preservation plans for two of the city’s most revered resting places: the First Presbyterian churchyard on East State Street and the non-denominational Mercer Cemetery across from the Trenton Transit Center. In the case of the former, our plan has assisted in the 2024 award of a $750,000 National Trust for Historic Preservation grant for the rehabilitation of this historic burial ground (see press release here). We have also recently designed and installed historic interpretive signage at Locust Hill Cemetery, Trenton’s oldest surviving African American burial ground, located on Hart Avenue.

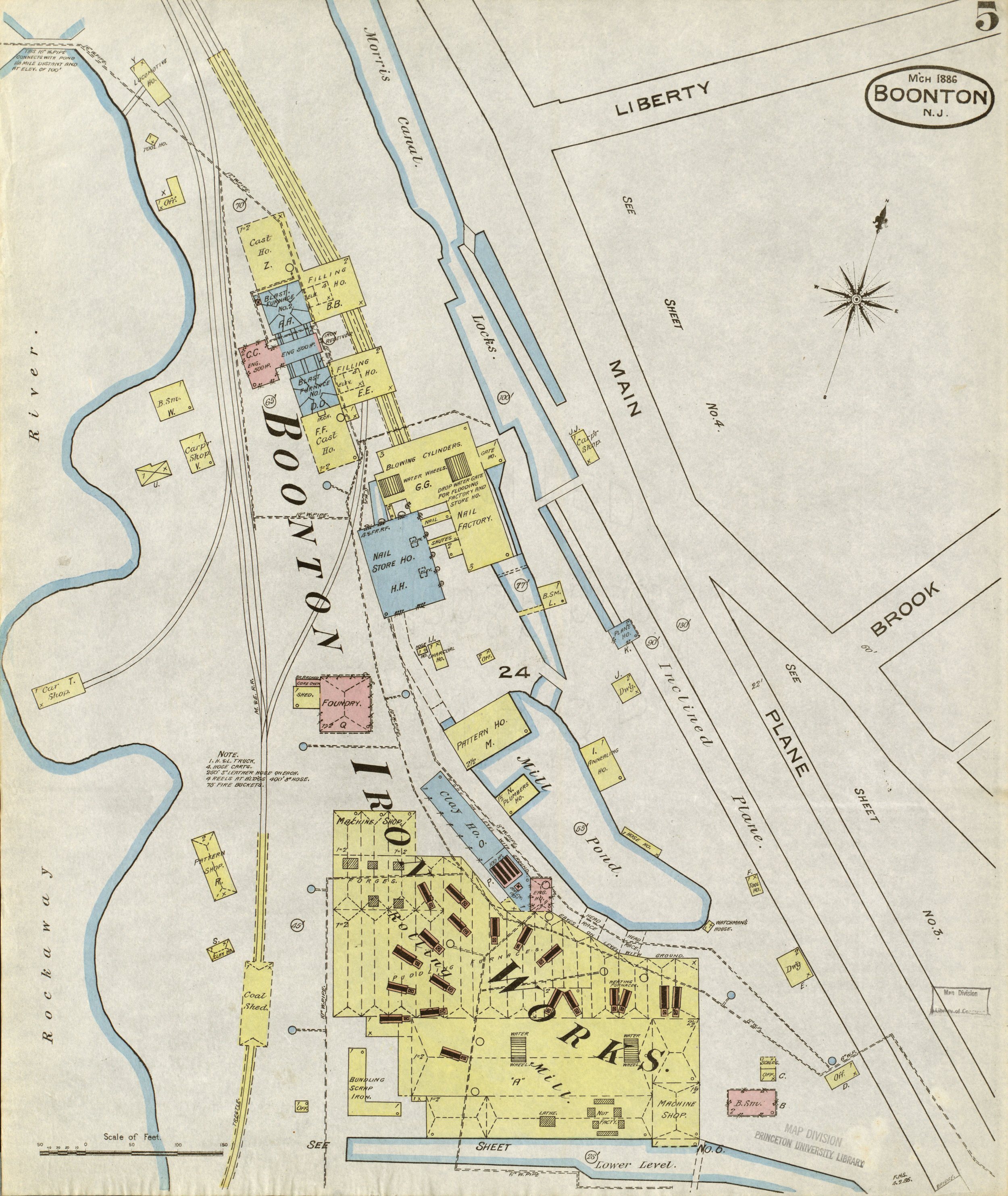

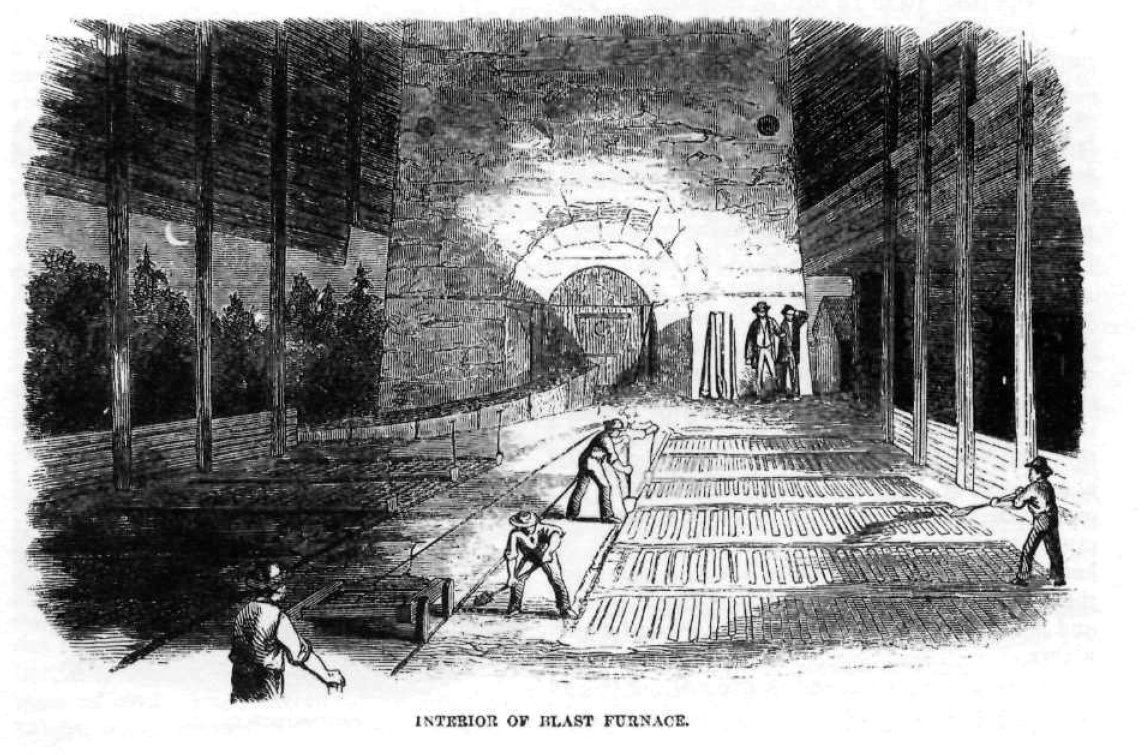

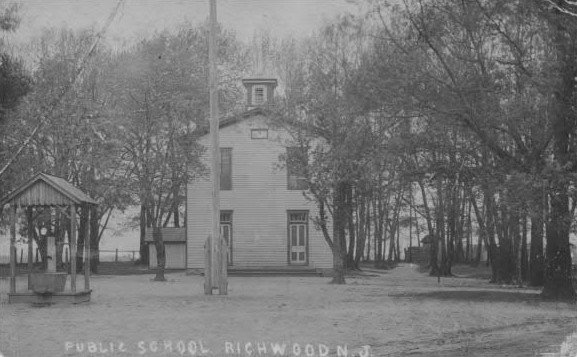

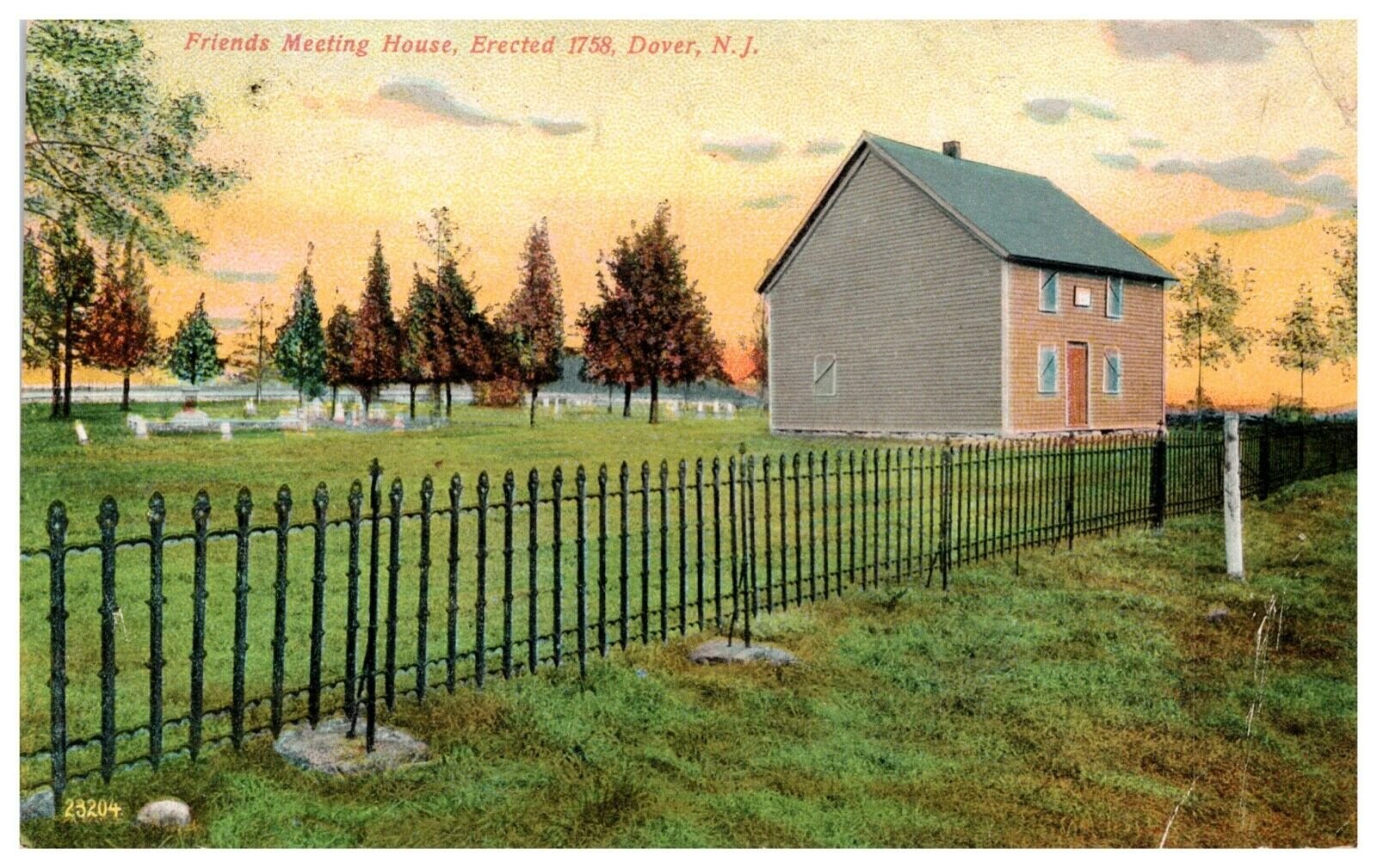

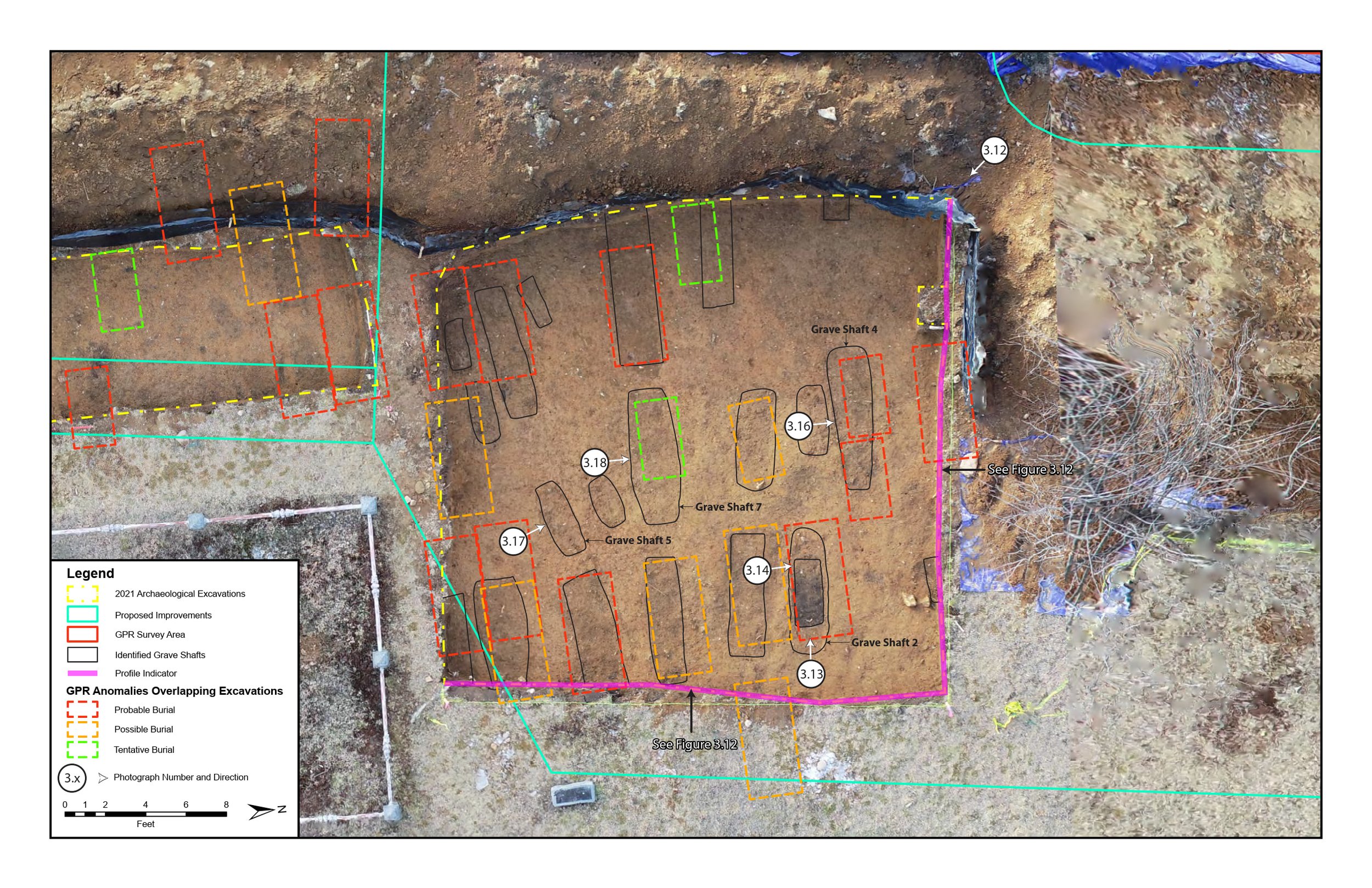

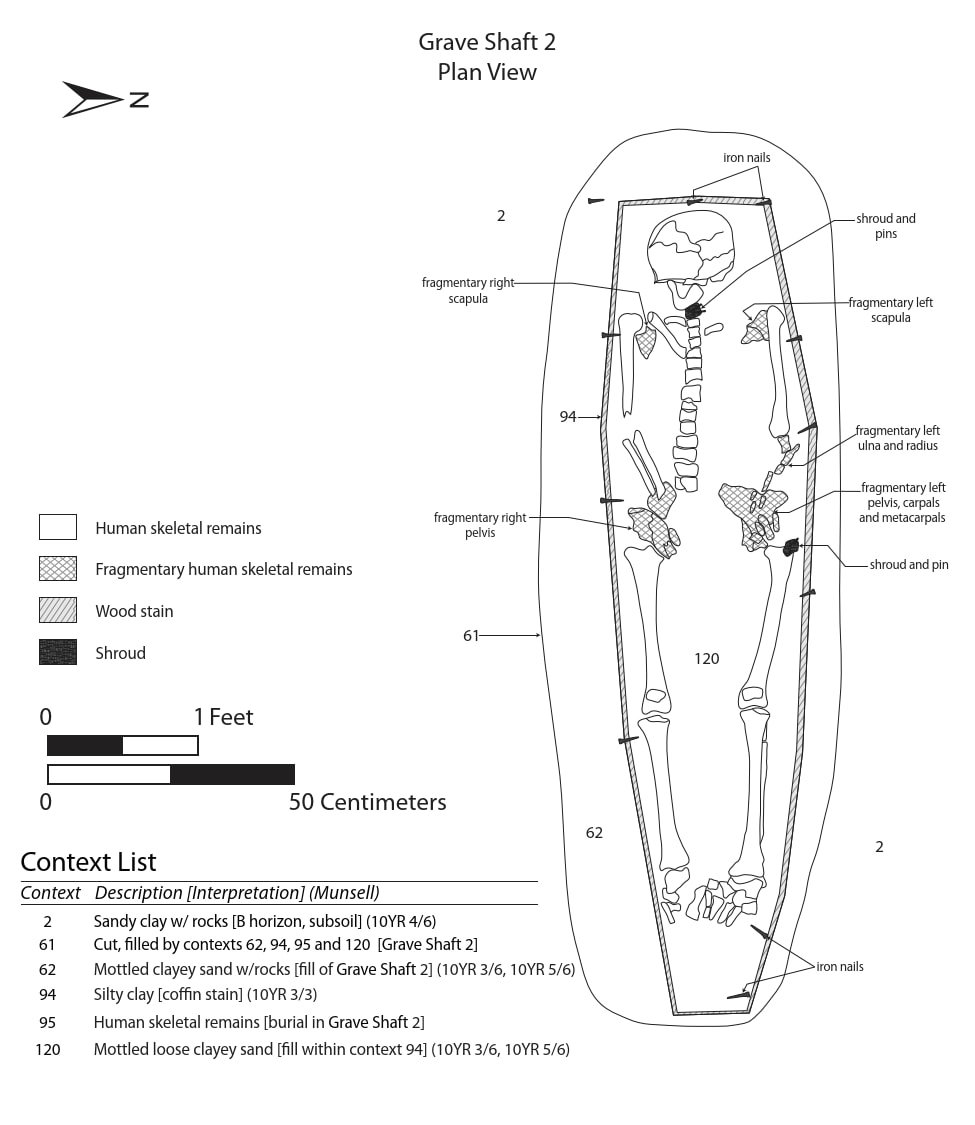

Elsewhere in New Jersey, at the 1758 Randolph Friends Meeting House in Morris County, we have undertaken ground-penetrating radar survey (with Horsley Archaeological Prospection), coupled with excavation, to identify and avoid unmarked graves in the Quaker burial ground ahead of a new parking lot (Randolph Friends homepage). At the other end of the state, outside Swedesboro, we are presently engaged resetting stones in a grave marker restoration project (with Lodestone Conservation) and completing GIS-based cemetery documentation at the 18th-century Moravian Church near Oldmans Creek. The first of these undertakings is being supported by the meeting house and grant funding from the Morris County Historic Preservation Trust Fund; the second by the Gloucester County Historical Society and the New Jersey Historic Trust.

![22023 Photograph 1.1 [22023-D1-002].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54eb7fcce4b0a4e937b40d71/1718133832734-STVB4KTOQC1K9KWYU1UN/22023+Photograph+1.1+%5B22023-D1-002%5D.jpg)

![22023 Photograph 3.7 [22023-D1-047].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54eb7fcce4b0a4e937b40d71/1718133834657-YQD41YA6S5LKWQREBE1O/22023+Photograph+3.7+%5B22023-D1-047%5D.jpg)

![22023 Photograph 3.8 [22023-D2-001].jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/54eb7fcce4b0a4e937b40d71/1718133835189-A08XHAK0VOLQ68DWXZXA/22023+Photograph+3.8+%5B22023-D2-001%5D.jpg)