Between 2023 and 2025, Hunter Research conducted archaeological investigations and architectural documentation at Ridgewood Water’s Cedar Hill Well Field in Wyckoff Township, Bergen County, New Jersey. This work was performed in conjunction with Ridgewood Water’s application for New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP) clean water funding to construct new per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) water treatment facilities. The project focused on the historical and architectural significance of the existing artesian wells and the archaeological importance of the underlying land, formerly the site of a mid-18th-century farmstead. NJDEP’s Division of Water Quality and the New Jersey Historic Preservation Office coordinated and oversaw this work.

Intensive-level architectural surveys recommended the Cedar Hill Well Site as eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. Ridgewood Water began supplying northern New Jersey municipalities in the early 20th century, establishing the Cedar Hill Well Field in the early 1930s to support suburban growth in western Bergen County. Concerned about the physical appearance of its facilities, Ridgewood Water designed the well field as a series of a half-dozen castellated, Gothic Revival-style stone and brick well houses within a park-like landscape. Advised by Hunter Research, Ridgewood Water has avoided demolition of any of the park’s original buildings, walls or landscape features, and designed the new PFAS facility with complementary neutral colors and vegetative screening.

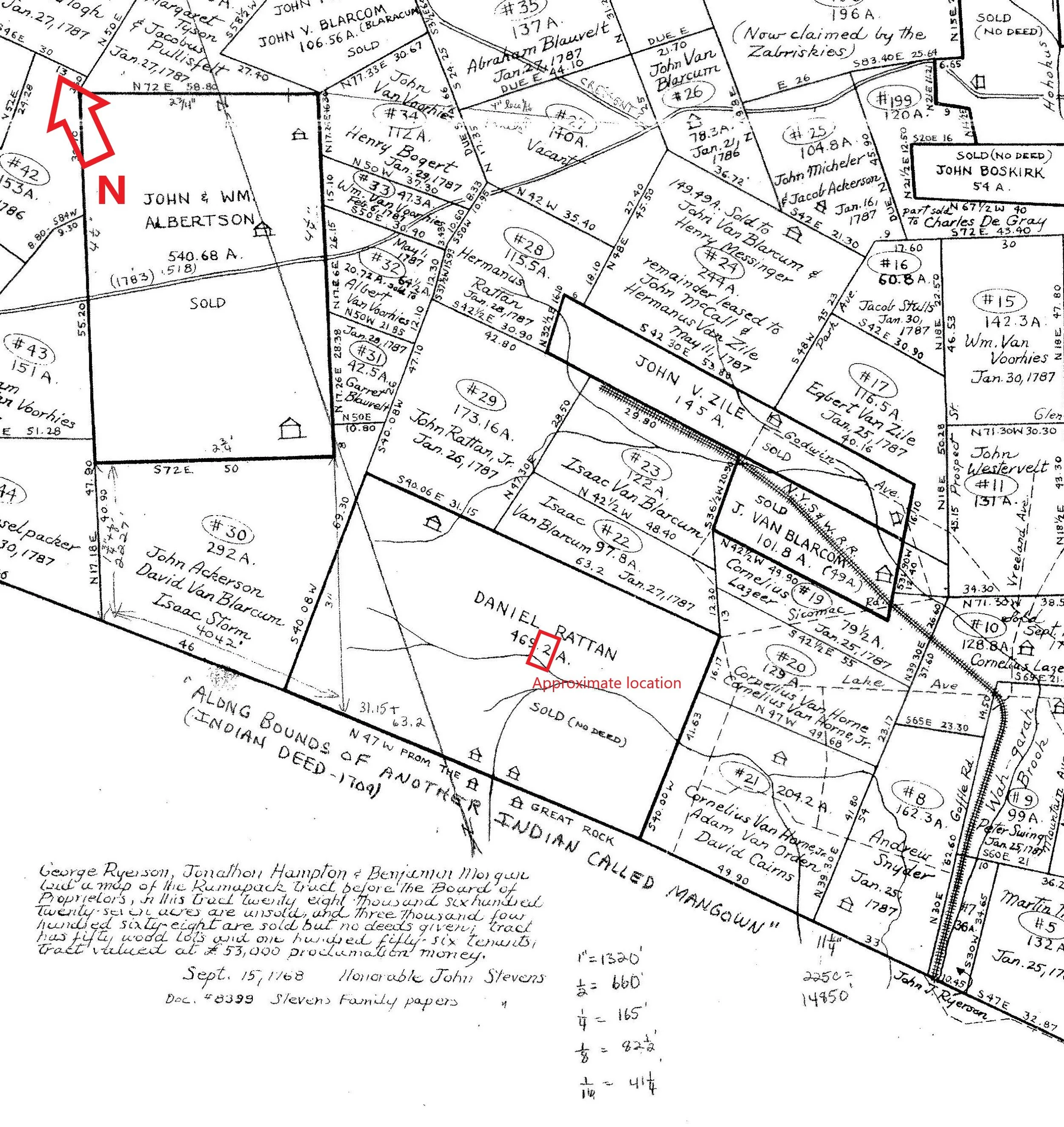

Archaeological surveys of the well field property unexpectedly produced a substantial number of 18th- and 19th-century artifacts—such as pottery, glass, pipe stems and building materials—that suggested an earlier domestic occupation of the site. Research identified the earliest resident as Daniel Rutan, a French Huguenot immigrant who settled in the area in the mid-1700s and established a homestead there. Hunter Research completed a program of archaeological data recovery at the site prior to the construction of the new PFAS treatment building, which will sit atop the footprint of the Rutan house’s stone foundations. Archaeologists recovered approximately 4,500 artifacts, among which are sherds of English Staffordshire and French Saintonge slipware made in the 17th and 18th centuries, providing a possible material culture link to the Rutan family’s French Huguenot heritage.

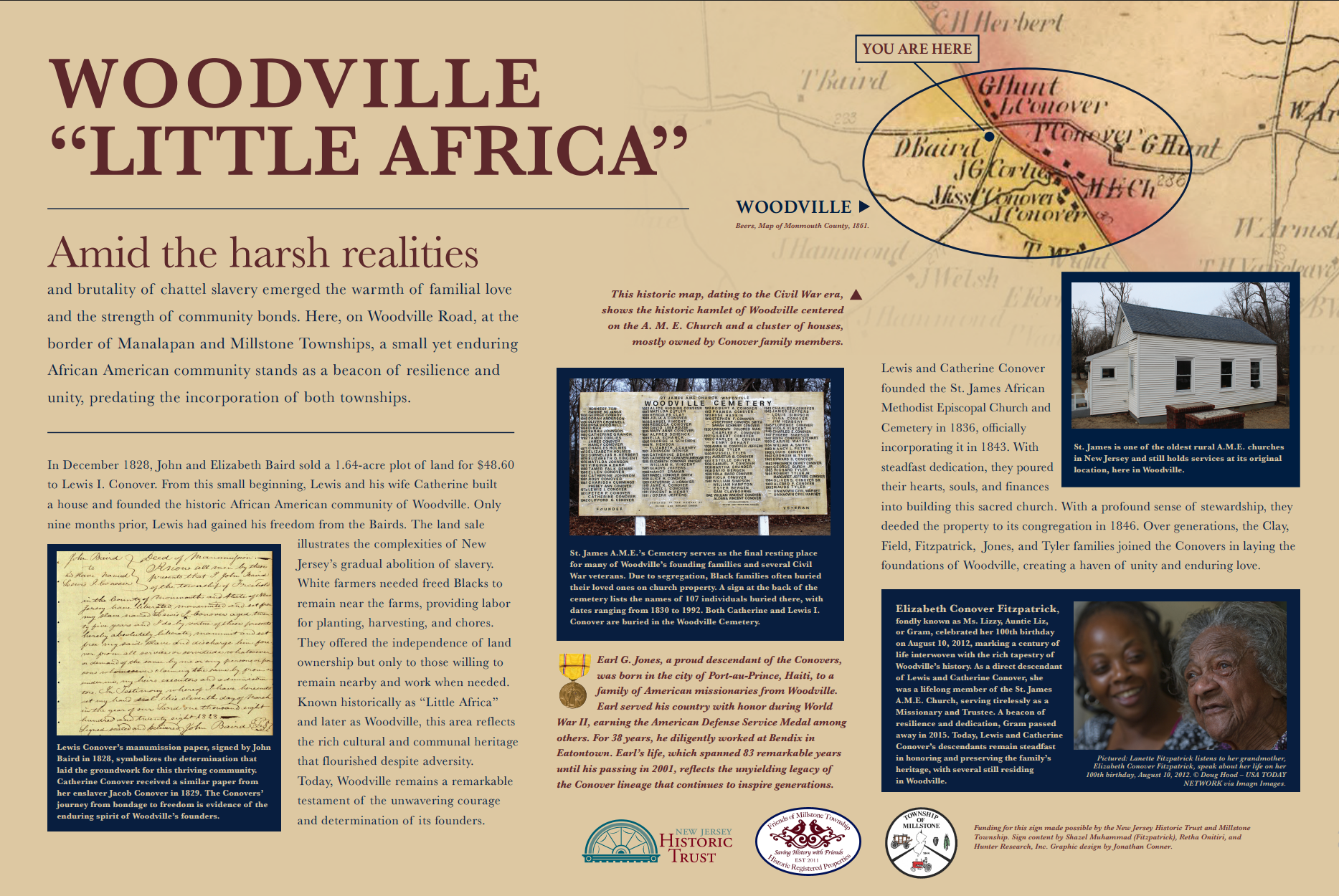

Hunter Research has designed an interpretive sign that will soon be installed at the Cedar Hill Well Field, as well as at Ridgewood Water’s offices and at the Wyckoff Library. More information about the project can be found in a Ridgewood Water-hosted webpage, which includes a blog that followed along with the archaeological investigations.